It was Kindergarten Round-up when my oldest daughter (now in 5th grade) was offered the opportunity to learn a string instrument. Among the plethora of solicitations (“Buy a yearbook now and SAVE!” “Join PTA today!” “Don’t forget your child’s lunch account!”) we found ourselves at a table surrounded by various string instruments, except they were kid-sized versions—a miniature violin, a tiny cello, and a baby bass. The two women at the table enthusiastically told us about a special strings program the school offered to all its students, starting as early as kindergarten. The program required dedication, parental-involvement, and willing learners. They warned us, it wasn’t something to walk into lightly. I glanced down at my daughter; her eyes were wide and bright with excitement as she looked at the instruments, a smile playing at her lips. The two women, capitalizing on the obvious interest, introduced her to each instrument, playing a bit for her so she could hear the sounds and letting her pluck a string or two. My daughter immediately loved the deep sound of the viola and I loved hearing that odds of a scholarship for a violist were much stronger as there were a lot less viola players. “So, what do you think?” I asked my daughter. Immediately, without hesitation, she said, “I want to play the viola. Can I do it, mommy?” And so began our viola journey.

Over the next four years, we navigated the journey side-by-side. She attended a group class once a week and practiced at least four times a week at home. I loved watching her play – the concentration she held between her brows, the smile that emerged at the end of a song. I remember her first solo performance; tears ran down my face and a great sense of pride and happiness filled me. This was it, I thought. My girl has found her “thing”. I gifted her viola necklaces, viola Christmas tree ornaments, a special viola bag for her stuff – all to remind her: She was a violist.

home. I loved watching her play – the concentration she held between her brows, the smile that emerged at the end of a song. I remember her first solo performance; tears ran down my face and a great sense of pride and happiness filled me. This was it, I thought. My girl has found her “thing”. I gifted her viola necklaces, viola Christmas tree ornaments, a special viola bag for her stuff – all to remind her: She was a violist.

By the end of her third-grade year, my daughter was progressing steadily; she was taking on more challenging pieces and had attended a week-long camp. It wasn’t until we moved houses and changed school districts that things started to change. We found a top-notch instructor for private lessons and enrolled in our new district’s after-school orchestra. She became fickle about the viola. She came to dread going to practice and we left her new instructor’s house, more often than not, frustrated, mad at each other, and disappointed. She told me she wanted to give up the viola, she asked to stop playing. But I continued to push it, convincing her we just had to get used to the new way of things, that she loved the viola, remember?

And so we soldiered on for the next year – with me desperately hanging on and her obliging at the very minimum to stay involved. It was clear to me her heart wasn’t in it, but I couldn’t let it go. She had worked all this time at it—for five years!—we had spent countless hours practicing, money for lessons, rentals, and camp and it was good for her academics and self-esteem (right?), never mind the potential scholarship opportunities, and, oh yeah, she was really good at it too!

I watched her at her final performance that school-year – gone was the concentration, determination, and joy I once saw. Instead, it was replaced with the resigned look one wears when doing a chore. I asked her what she thought of the performance; she shrugged and asked if we could go get fro-yo. It broke my heart.

I watched her at her final performance that school-year – gone was the concentration, determination, and joy I once saw. Instead, it was replaced with the resigned look one wears when doing a chore. I asked her what she thought of the performance; she shrugged and asked if we could go get fro-yo. It broke my heart.

That summer, we had a few lessons but I stopped pushing for her to practice. At end of our last lesson, I asked her, “Do you want to play the viola anymore?” Peering at her in the rear-view mirror, a look of worry swept over her face and she replied, “Well, I know you really want me to play…” I took a deep breath and asked, “Honey, does it make you happy to play? Do you like it?” She hesitated, looked down, and responded, “No, not anymore.” And that was it; I knew we had arrived at the end of our viola journey. We packed up the viola and returned it the next day. I cried. She was dry-eyed.

I asked her what she wanted to do as her extra-curricular activity now. She talked about how much she loved making videos on her tablet and thought it would be fun to take a class so she could learn more. I found a place that had just opened by our house, an academy that offered lessons on digital design. I enrolled her in the videography class. She was excited and nervous on her first day; we were both encouraged by the friendliness of her instructor as she introduced herself and showed us around the studio. I sat in the waiting room and half an hour later she returned to me, a bright smile on her face. We bid her instructor good-bye, and as soon as we go out the door my daughter responded with a squeal of delight and started a rambling monologue that only another 10-year old girl could keep up with. She was literally standing on the tips of her toes as she talked, excitement pouring out of her, her eyes shining bright. There it was – the passion, the joy, the happiness – that had been missing from her viola playing for the last year, longer if I was really being honest with myself. She was “sparking”.

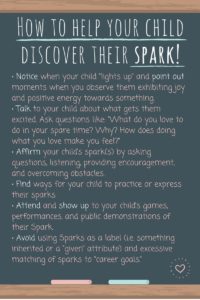

When we are “sparking” we are utilizing our “Sparks” or the inner passions, skills, and strengths that are discoverable in all of us. Sparks are deeper than activities we enjoy – they are a source of motivation that encourage us to grow and contribute to the world. Some common examples that youth site as their Sparks include: caring for pets, drawing and painting, sports, volunteering/giving back to others, learning a subject, building, making friends, or being outdoors. Spark Champions are those who help identify and grow youth sparks, channeling energy toward pursuit of positive passions and interests. Youth’s sparks can shine brightly or dimly depending on whether they have Spark Champions.

There are many benefits for youth who have at least one Spark and have adult support in growing it:

- Higher grades and better school attendance

- Better social skills

- Better health

- More likely to volunteer to help and to take care of the earth

- More likely to have a sense of their life’s purpose

As parents, we have our own set of hopes and expectations for our kids regarding their Sparks. Sometimes, it’s because we sparked in an area—a sport, a hobby, an interest—and we want our kids to experience what we felt when we were engaging in our Spark, so we enroll them in soccer “just like dad” or get them into a tutu at two because “mommy was a ballerina too”. Or maybe we struggled with our own Spark discovery—but we always wanted to be a musician or a basketball player, so we sign our kids up for those activities so they won’t miss out. Or maybe our children show a natural inclination towards a sport or an art, so we must drive them in that one area so as not to deprive the world of the next Tiger Woods or Gabby Douglas or miss out on  free college. We have good intentions, but we can really interfere with true Spark discovery (case in point). I’m not saying that we should pull our kids from every extracurricular activity at the first eye roll or tear, but we must keep the lines of communication – and our minds – open. We must set our own expectations aside and let our children discover what makes them, not us, truly happy and motivated.

free college. We have good intentions, but we can really interfere with true Spark discovery (case in point). I’m not saying that we should pull our kids from every extracurricular activity at the first eye roll or tear, but we must keep the lines of communication – and our minds – open. We must set our own expectations aside and let our children discover what makes them, not us, truly happy and motivated.

Last month, I attended the Winter Showcase at my daughter’s academy. Dressed in her finest for her first “red carpet interview”, she proudly told the interviewer about the movie she would premiering that evening, a spinoff of Alice in Wonderland. Later, she confidently described the process she used to make the movie, the challenges she faced during production, and her favorite part of the experience. Then, she premiered her two-minute video, smiling happily as we all laughed and cheered at the end. As she made her way back to her seat, she looked at me and raised an eyebrow, a clear “well, what did you think?” gesture. I gave her two big thumbs up and a smile to mirror her own. After all, they give scholarships for digital design, right?

At Camp Fire, our programs are designed to aid in spark discovery creating opportunities for youth to express and test their various Sparks. Our staff are trained to serve as Spark Champions—they understand the ways to know, name, and nurture each child’s spark

Nikki Roe Cropp is the Director of Program Quality for Camp Fire First Texas. Nikki brings more than fifteen years of nonprofit experience to the council, including her work as an overnight camp counselor in college. In her role she evaluates, modifies and evolves curricula for Camp Fire programs and also supervises professional development for program staff. Nikki has two daughters who participate in Camp Fire programs. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in psychology from Kansas State University and an Urban Nonprofit Management Graduate Certificate from the University of Texas at Arlington.